By Amalia Verzola

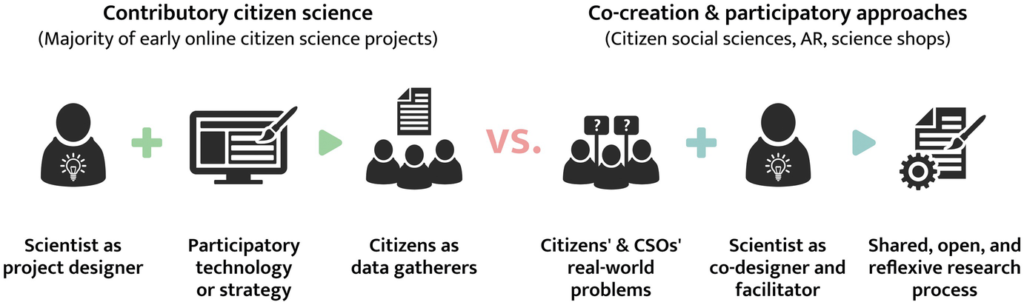

Until recently, citizen science was mostly promoted as a simple and effective method to boost the scale and relevance of data collection in a number of disciplines, such as astronomy, biology, environmental sciences, health sciences or urban studies. Digital technologies, in fact, have increasingly facilitated the collective generation of data, and this is even more evident if we take a look at how crowd-sourced data initiatives have mushroomed across a variety of research fields. Despite the huge potential of citizen science, most initiatives working with non-professional researchers still include them only in certain specific steps of the research process, rather than from the very outset. In fact, citizen scientists tend to mainly contribute to data gathering, while being excluded from research design, analysis and interpretation. How to ensure systemic participation of citizens in all research phases? How can citizens become involved in more phases of the research process?

Over the last decades the democratisation of innovation processes, as well as the strengthening of societal participation in research, has been widely promoted by funding bodies such as the European Commission, which has been streamlining in research and innovation funding programmes the benefits of opening up science to society. This is why the concept of Responsible Research and Innovation has been put across, namely to detect effective solutions to specific issues affecting communities, promote a multi-directional approach to problem solving, and boost the participation in research and innovation processes of diverse actors. This concept is now under the umbrella of Open Science, a policy priority for the European Commission, and whose aim is nurturing research and innovation processes by involving diverse actors from across academia, industry, public authorities and citizen groups. The ultimate goal? To enhance both creativity and trust in science. All of this translated into increasingly participatory research and innovation processes featuring various stakeholders with diverse knowledge, backgrounds, and interests. Such processes are described with the concept of co-creation. Why is it co-creation relevant to citizen science, too?

According to the ECSA ten principles of Citizen Science, “citizen scientists may, if they wish, participate in multiple stages of the scientific process. This may include developing the research question, designing the method, gathering and analysing data, and communicating the results”. When it comes to co-creation in citizen science, lessons can be drawn from a long tradition of related practices such as participatory action research, where a diversity of non-professional and non-academic researchers can be fully involved in the investigation process. To go beyond a purely contributory vision of citizen science, non-professional researchers should be included as much as possible in the research process, from research question formulation to evidence-based research outcomes, and this is why Step Change has planned a series of tasks to ensure a wide-ranging participation of them in all phases of the implementation of the Citizen Science Initiatives, including the very first ones.

(Source: “Participation and Co-creation in Citizen Science”, in “The Science of Citizen Science”, Springer, January 2021)

For instance, the Citizen Science Initiative on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, led by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, will invite citizen scientists to review and give feedback on the data collection tools designed to collect data from patients participating in the translational research experiment, such as questionnaires and diaries. The tools will be modified in response to citizen scientists’ feedback. On the other hand, the experiment had already been evaluated and considered of scientific interest to patients with diabetes, endocrine diseases and metabolic disorders by the patient and public involvement group of the Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism in the Radcliffe Department of Medicine at the University of Oxford.

The Citizen Science Initiative on wildlife monitoring in Slovenia, coordinated by the University of Primorska, will invite hunters and non-hunters to collect data about wildlife presence via the app for mobile devices. In this framework, the Hunters Association of Slovenia was invited to co-design the app and data collection protocol, altogether with the University of Primorska and an external company featuring previous experience in wildlife monitoring app programming. The app was co-designed through on-line meetings in autumn 2021, and piloted on a sample of hunters and wildlife researchers. Co-designing also involved a quiz for wildlife identification, which was piloted and then integrated into the app. The protocol for data collection, which also included camera trapping in pilot areas, was co-designed as well, and the Hunters Association of Slovenia provided extensive advice about data collection through camera trapping.

As for the Citizen Science Initiative on energy communities in Germany, led by WECF, citizen scientists were invited to a method co-creation meeting with the core team of the initiative. Citizen scientists provided feedback on the content of lifestyle questionnaires and workshops to be conducted during the data collection phase. During the meeting, engaged citizens could interact with researchers and civil society representatives working in the fields of community energy and citizen participation in the energy transition. The involvement of citizen scientists, among whom was also present a member of an energy cooperative and tenant electricity user since last January, will enrich the comprehensibility of the questionnaire.

Citizens were involved in the designing of tools in Uganda as well, where ARUWE is leading the Citizen Science Initiative on off-grid renewable energy in agriculture. During both the planning and the research design phase, the citizen scientists contributed to the sketching of the tools, and this was done through the means of consultative meetings organised at the local level and featuring different cooperative representatives, local leaders and the other stakeholders. The citizen scientists provided in-depth information about the tools as well as the target groups, while also participating in the preliminary testing of the draft tools which were incorporated in the research protocol.

Last but not least, the University of Tor Vergata, leading the Citizen Science Initiative on infectious diseases preparedness, not only will involve young citizens such as high school students in the process of gathering data stemming from past citizen science experiences in order to develop a taxonomy, but at a later stage will also involve several stakeholders such as General Practitioners, policymakers and citizen organisations in the active process of designing an effective strategy for facing future epidemics and pandemics. In the last phases of the initiative, in fact, several workshops will be carried out, during which citizen scientists will be given the opportunity to co-draft a document explaining how citizen science may be adopted and developed to increase the level of preparedness of Italy for possible future infectious diseases outbreaks.