What makes an expert?

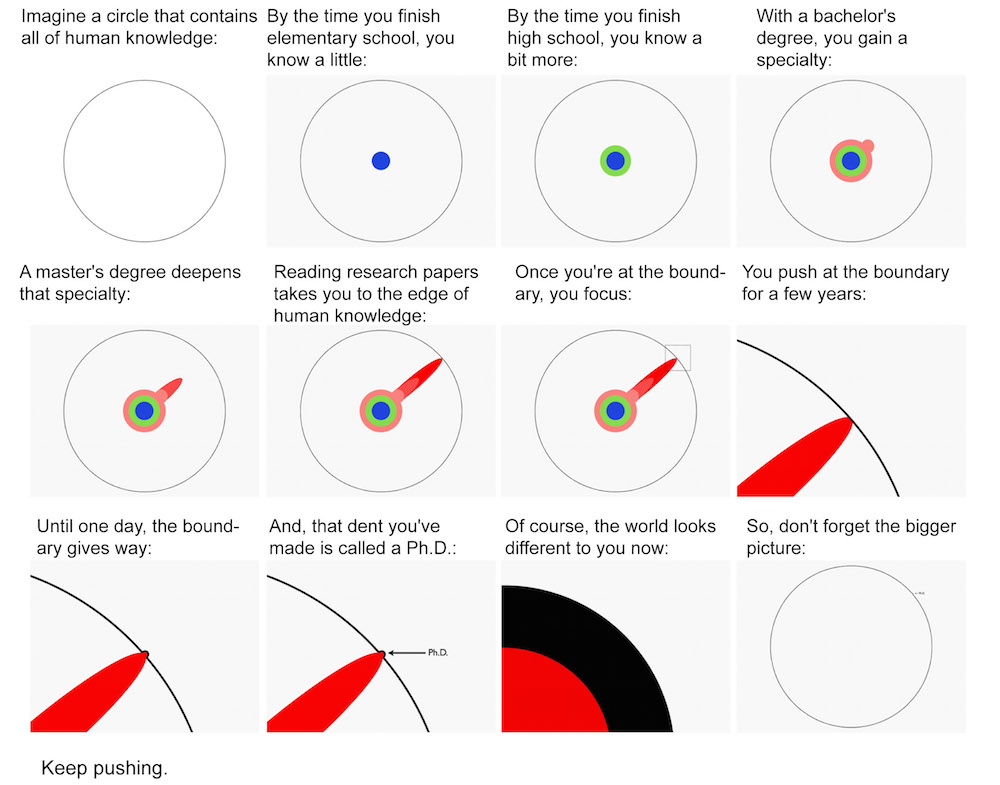

Science is traditionally built on “specialism”; from an early age we are all forced to make decisions about what we want to dedicate our limited brain power to, from GCSEs, and A-levels (or the equivalent) in schools, to perhaps undergraduate degrees, training and vocational courses later in life. For researchers, this usually means fully committing to the “academic treadmill”, dedicating their lives to the pursuit of knowledge in a very specific field, continuing their education through Master’s and Ph.D. programs, and on to the world of professional research. However, through this process of specialisation, academics can inevitably develop “blinkers” for the rest of the world, as demonstrated in the illustration below by Matt Might, a Senior Lecturer from Harvard Medical School.

However useful this specialised knowledge is, there is the ongoing risk of a researcher “not seeing the woods for the trees” or seeing problems as experiments in a petri dish, outside the realms of real life. This may be invaluable for figuring out the fundamentals of a problem, but in a world of “wicked problems”, issues with no clear single cause or solution, perhaps a more well-rounded approach is now required.

Perhaps this is where the paths of knowledge and wisdom deviate. Where knowledge is the means of knowing “why” something happens; wisdom allows us to know “how” to use this information in a more practical sense, and this is where the experience of “non-traditional” and “non-academic” experts should be utilised.

Non-academic experts are individuals who have practical experience and expertise in a particular field or subject but do not necessarily have formal academic training or qualifications in that area. They may be professionals working in industry, government, non-profit organisations, or other areas outside of academia. They are often referred to as “practitioners“.

The role of Non-Academic Experts

Non-academic experts can bring a unique perspective and valuable insights to research projects, as they often have practical experience and real-world knowledge that can complement the theories and methods of academia. They can also be valuable partners in collaborative research projects, as they may have access to resources and data that are not readily available to academic researchers, and this can be invaluable in shaping the direction and focus of research.

This approach is readily taken up by citizen science initiatives by involving stakeholders from quadruple helix (science, policy, industry, and society), in multiple stages of the research process, through experimental design, data collection, and eventual dissemination of research findings.

Non-academic experts are often professionals in their own field, but this is not necessarily the case. For many, knowledge may come from just a general interest in a subject, or be derived from an individual’s “lived experience”. Perhaps with those with an interest in ecology and the environment are perceived as the exemplar, as many people have interests that either overlap with this topic (such as bird watchers, hunters, fishers, and hikers), or as it is a topic that the general public hold quite dearly. However, these expertises could extend to other fields of research, such as the lived experience of those with a specific disease, or living within communities that are facing a real-world issue (such as urban development or pollution).

The inclusion of these “non-professional” people in a research study may require additional communication and outreach efforts, as well as considerations as impositions on people’s time and availability, as these individuals would most likely be participating around their ongoing daily lives. However, in modern research, the scientific community hopes to build a better relationship with society, especially within the practice of citizen science. It is also important to build in a way that recognises the efforts of these individuals and the input they provide.

In a nutshell, non-academic experts have a lot to offer the research community and can play a valuable role in advancing knowledge and solving real-world problems.

A word from our partners- University of Primorska- Wildlife Conservation in Slovenia

In Slovenia, hunters have been collecting data on wildlife for decades – without knowing it or calling themselves citizen scientists. They are special group experts with traditional knowledge who systematically, continuously, and responsibly collect field data regarding wildlife. The entire process of hunter education is a high-quality, thorough, lengthy, systematic approach, and based on appropriate andragogical–pedagogical knowledge that ensures that hunters are qualified to participate in wildlife monitoring by collecting data and samples.

For this reason, Slovenian hunters have always been valuable collaborators of wildlife researchers. For example, in cooperation with researchers, they have conducted monitoring of carnivore species: grey wolf, brown bear, and Eurasian lynx. Estimation of brown bear census size has been improved by the collection of thousands of faecal samples for genetic monitoring or a much more reliable determination of exact numbers of bears.

Additional sample collection of European roe deer, wild boar, and Alpine chamois has led to interesting research projects/programs and monitoring aimed at determining the population structure and reproductive potential of ungulates.

The inclusion of hunters as citizen scientists in the project is based on three major contributions:

- the provision of data on animal occurrence and observation, focusing on traits relevant to understanding population status and trends;

- the systematic collection and provision of images from camera traps, which, with subsequent centralised statistical processing and the use of protocols that have emerged in the European region, will provide a much more reliable estimate of wildlife abundance or population density;

- collection of samples for various research purposes (for example the establishment of a gene bank for various game species, which could also be housed in the new Slovenian hunting centre and would enable in-depth genetic research and monitoring).

The common goal of Slovenian researchers and hunters is to develop modern monitoring methods that, with the involvement of citizen scientists, will provide a much more accurate estimate of population size.

Additional Reading:

Viola, B.M., Sorrell, K.J., Clarke, R.H., Corney, S.P. and Vaughan, P.M., 2022. Amateurs can be experts: A new perspective on collaborations with citizen scientists. Biological Conservation, 274, p.109739.

Groulx, M., Nowak, N., Levy, K. and Booth, A., 2020. Community needs and interests in university–community partnerships for sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education.

Bunders, J.F., Broerse, J.E., Keil, F., Pohl, C., Scholz, R.W. and Zweekhorst, M., 2010. How can transdisciplinary research contribute to knowledge democracy?. In Knowledge democracy (pp. 125-152). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

The featured image is taken from: