As the Step Change project reaches its final stages, the team at NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) who are investigating citizen science and participatory practices’ role in research into treatments for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) are visited by our evaluation team.

Step Change evaluators Luciano D’Andrea, of Knowledge & Innovation, a social research institute based in Rome, and Evanthia K. Schmidt, of Aarhus University in Denmark, visited the Oxford BRC team, including some of the citizen scientists, to discuss their experiences.

Luciano D’Andrea said:

“I saw that everything was well organised and in this final evaluation, I can see the enthusiasm citizen scientists showed to be more involved and that is a good sign for the future. We have to find structures to help them.

I believe that in many cases, citizen science could play a pivotal role. This kind of research is very much based on experience – life experience, the views of citizens with experience as carers, experience of the healthcare system.”

The analysis of the qualitative data that the citizen scientists have compiled will be presented at the European Citizen Science Association (ECSA) Conference in Vienna in April. There will also be a standalone paper that uses the data generated by the citizen scientists which will include their experiences of being part of the project.

In addition, the findings of the NAFLD (now renamed as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease – MASLD) study will be published. These will reveal that it is a nighttime disease and therapies should be targeted at night – the first time this has been demonstrated in humans.

Speaking of the value that the citizen scientists brought to the project, Co-investigator on the study and the Oxford BRC’s Theme Lead for Metabolic Experimental Medicine Professor Jeremy Tomlinson said:

“It’s been very rewarding. It’s important for scientists to engage with people who aren’t scientists because that way we get a much broader perspective on the research we do.”

“It allows us to understand what’s important to patients and the public and gives us an opportunity to work out how we can best get our message across, because each of the citizen scientists comes from a different angle, they each have their own motivations for why they want to be a part of research. As well as having the skills that we’ve taught them, they each bring their own individual skills, which means they can interpret and help analyse the data in a way that gives them a most relevant perspective for the general public.”

One of the six citizen scientists recruited by the Oxford project was Magdalen Wind-Mozley, who said: “I’ve benefitted a lot from this project – in addition to learning about NAFLD. Although I have been involved in research for several years, I had very little experience before of qualitative data analysis, and I’m keen to learn more about this aspect of research. I also now have a broader understanding of – and interest in – ethics, and the different kinds of ethics, not just our narrow European perspective.”

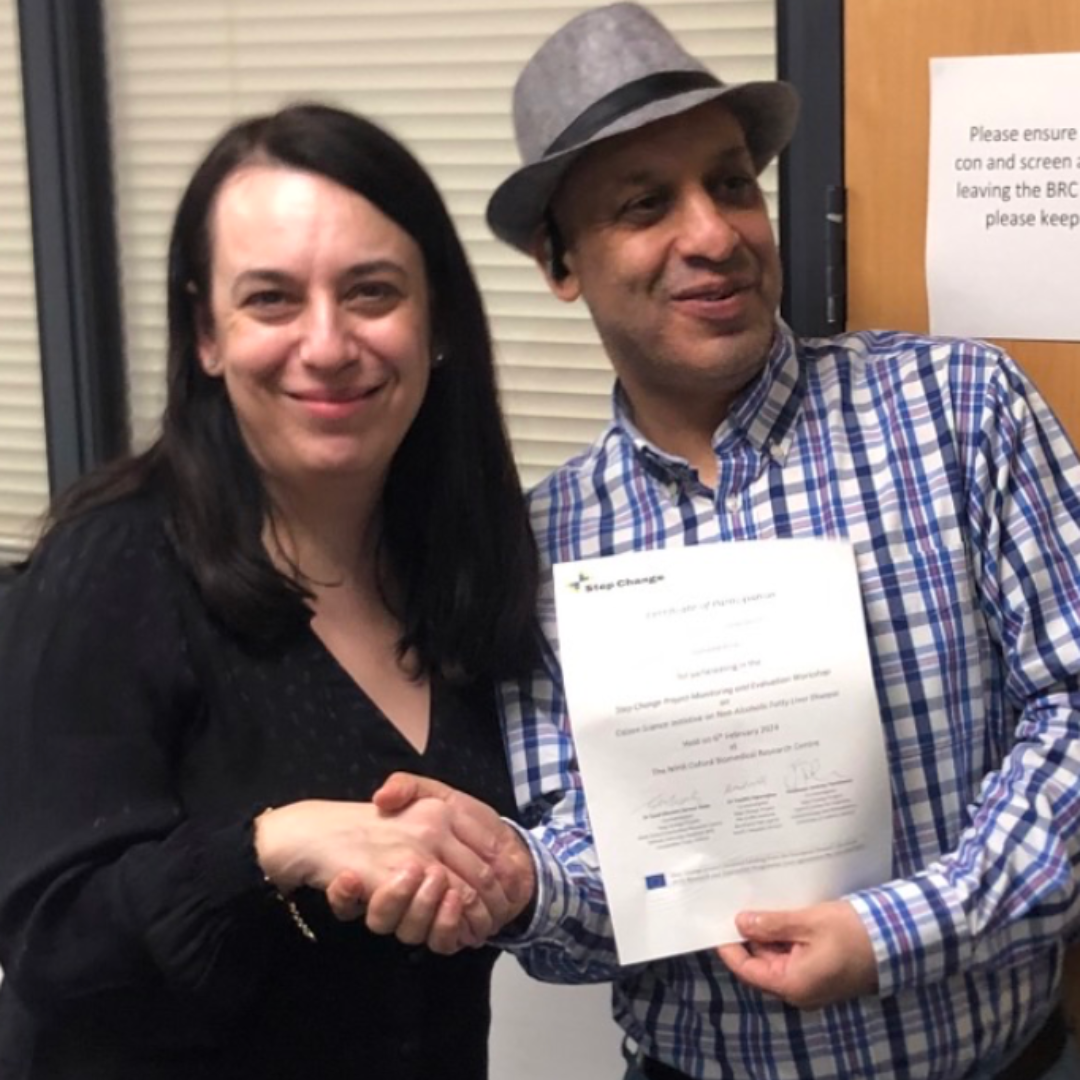

Another of the citizen scientists, Hameed Khan, added: “I got a real sense of empowerment. I realised that, in my own way, I am a scientist. I have the right to take an interest in science. I’m now more critical and able to question the research, data, and statistics. I now want to know where I can take these skills.”

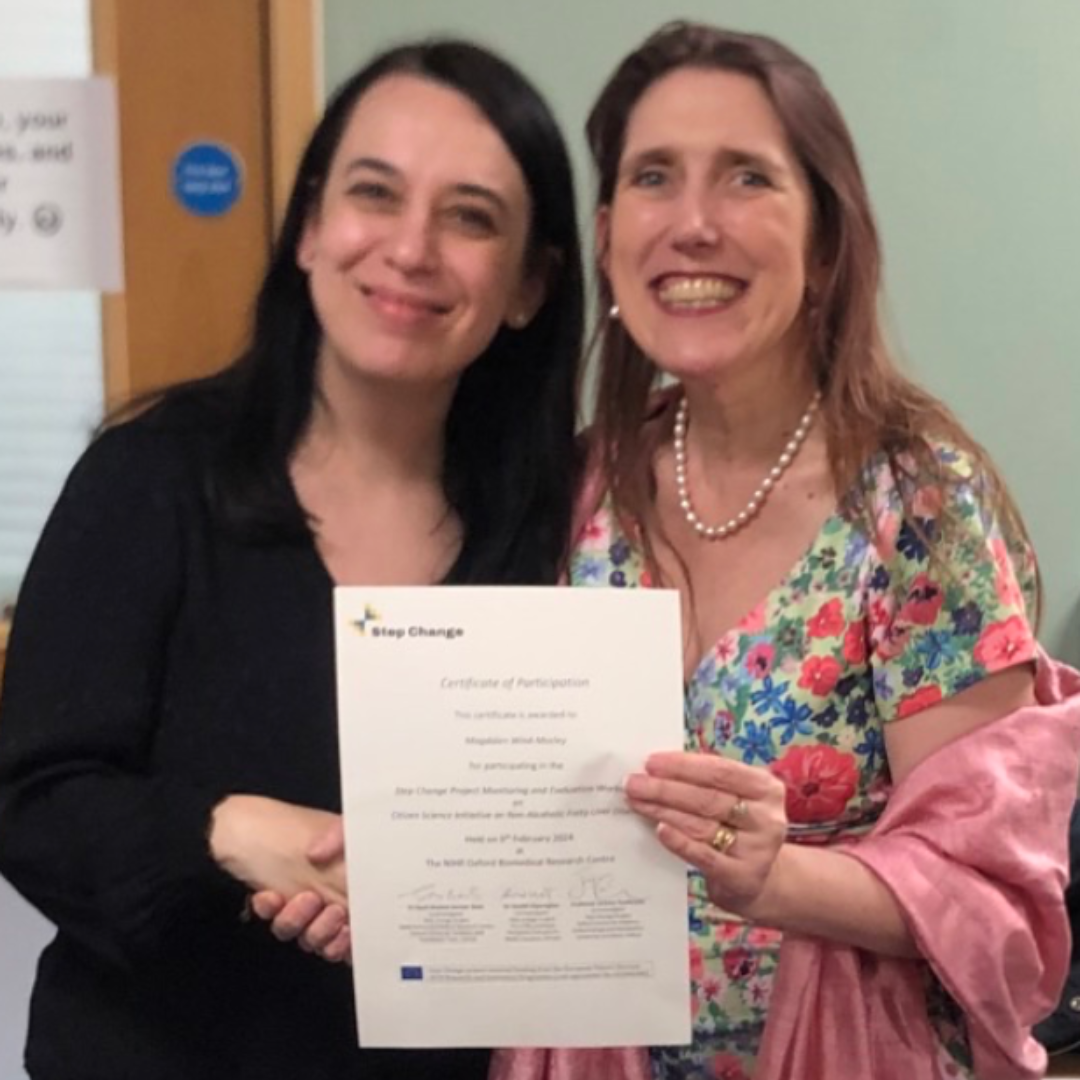

Vasiliki Kiparoglou from the Griffin Insitute with Magdalen Wind-Mozley

Hameed Khan

Zuzana Kalmarova, who travelled from Slovakia to participate in the workshop

To recognise their important contribution to the project, the citizen scientists were given a certificate.

The benefits of this citizen science approach include enhancing the skills of patient and public involvement (PPI) contributors, and during the workshop the citizen scientists floated the idea of them having a mentoring role for other PPI contributors. But one of the biggest questions was around sustainability and continuity, given that expanding the role of citizen scientists would be dependent on funding.

Dr Sarwar Shah, another of the Oxford BRC co-investigators, commented: “We’ve identified some crucial factors for the sustainability of the citizen science approach. Most important is communication – how to reach them, attract them and involve them, and afterwards keep their engagement. Next is infrastructure for developing their skills and opportunities, including training and a recognition of their contributions to knowledge-creation and incentives. They spend their time on a voluntary basis but what are the incentives for them to keep their involvement on a long-term basis.”

Click here to find out more about the work this CSI has done throughout the Step Change Project.